The Need for an Institutional History of the Supreme Court of India: Three Examples from the Early Court

One of my projects involves building a dataset of all reported decisions of the Supreme Court of India (SCI). A problem that I consistently encounter in my analysis is the lack of any record of the institutional history of the SCI. Gadbois’s classics on the history of the federal court and on the judges of the Supreme Court gives us some anecdotal information on some court procedure but is limited by time-period. Abhinav Chandrachud’s Supreme whispers (also based on Gadbois’ interviews), similarly has anecdotal information about how the court functioned, but even this is mostly eclectic and sparse. There seems to be nothing, on the lines of Perry’s classic work on the U.S. Supreme Court, that builds a historical account of how institutional rules and conventions in the SCI have changed throughout history.

My empirical analysis is thus limited by the lack of background knowledge about how the court functioned at the time each case that I examine was heard. To fully understand decision-making, we need to know how cases were allocated to panels, how these panels admitted cases and how opinions were assigned. The current rules of the court as well as common perceptions about the court process cannot substitute for a clear understanding of how the court’s process has changed over time. Even in the first thousand cases(1950-1959) in my dataset, I found several interesting deviations from current norms of the court– the Hyderabad Bench of the court, Even Panel Formation, and Seriatim decision-making.

Supreme Court of India in Hyderabad

The Constitution of India states that Delhi will be the site for the SCI. The Chief Justice of India, after receiving approval from the president, is allowed to create separate regional benches of the court. Recent commentators on the SCI have advocated for these regional benches and I had always assumed that the Court has never sat outside the capital. I was thus surprised to see three judgments pronounced by the “Supreme Court of India in Hyderabad” in the first year of the Court. These decisions were delivered by Justice Mahajan and two judges who are not part of the list of judges of the Supreme Court - Justice R.S. Naik and Justice Khaliluzzanan.

The only information I could find on these cases was in Gadbois’s book. Apparently, around 400 cases that were pending before the Nizam’s privy council in Hyderabad were transferred to the SCI after the Constitution came into force (p.27). Justice Mahajan led the bench due to his knowledge of Urdu, and two judges of the High Court of Hyderabad, Chief Justice R.S. Naik and Justice Khaliluzzanan, were appointed as ad-hoc judges of the SCI to dispose these pending cases. Gadbois says that Mahajan, under similar circumstances, also headed a SCI bench in Kashmir, but I could not find any case from this bench in my dataset.

Given the advocacy for regional benches, I was surprised how little attention is given to the fact that the court has actually sat in two other sites and had two ad hoc judges. Apart from the mention in Gadbois book and a few mentions in court websites, I could find no information about the two ad hoc judges or about the Court’s functioning in Hyderabad. The mechanism through which this was done is also unclear. Article 128 of the Indian Constitution mentions that a retired judge of the SCI or High Courts can be appointed ad hoc, but it is unclear if this provision was used here.

Even Panel Formation in the SCI

As Nick Robinson has pointed out in his analysis, panel sizes have changed a lot from early days in the SCI. Early on, most cases of the court used to be heard by large panels of either three or five judges. Due to the marked increase in workload in the following decades, most cases in the SCI now are heard by a panel of two judges.

Despite the importance of panel selection on judicial decision-making, it has received very little scholarly attention. Gupta’s (1995) book is the only one I know of which looked at systematic bias in the formation of benches. Due to the fact that the Chief Justice of India as the “Master of Roster” has unbridled decision in panel formation in the SCI, they do not have to give public reasons for their choice. We thus have no information on why particular people sit in given panels, an issue recently raised at the press conference of SCI judges.

We also do not seem to know why a panel of a particular size was formed in a given case. Beyond the constitutional norm of 5 judge panels for “Substantial questions in the interpretation of the constitution”, and current rules mandating certain cases to be heard by atleast 3 judges, we do not know the norms governing panel size. Obviously, one would need a larger panel to overrule a previous decision of a smaller one, but it is unclear what triggers the formation of this larger panel. Presumably, a case is listed before the larger panel, if a smaller panel recommends it, but this is not always the case. For example, in the Sabrimala review case was listed directly before a 9 judge bench, without a reference from the smaller bench.

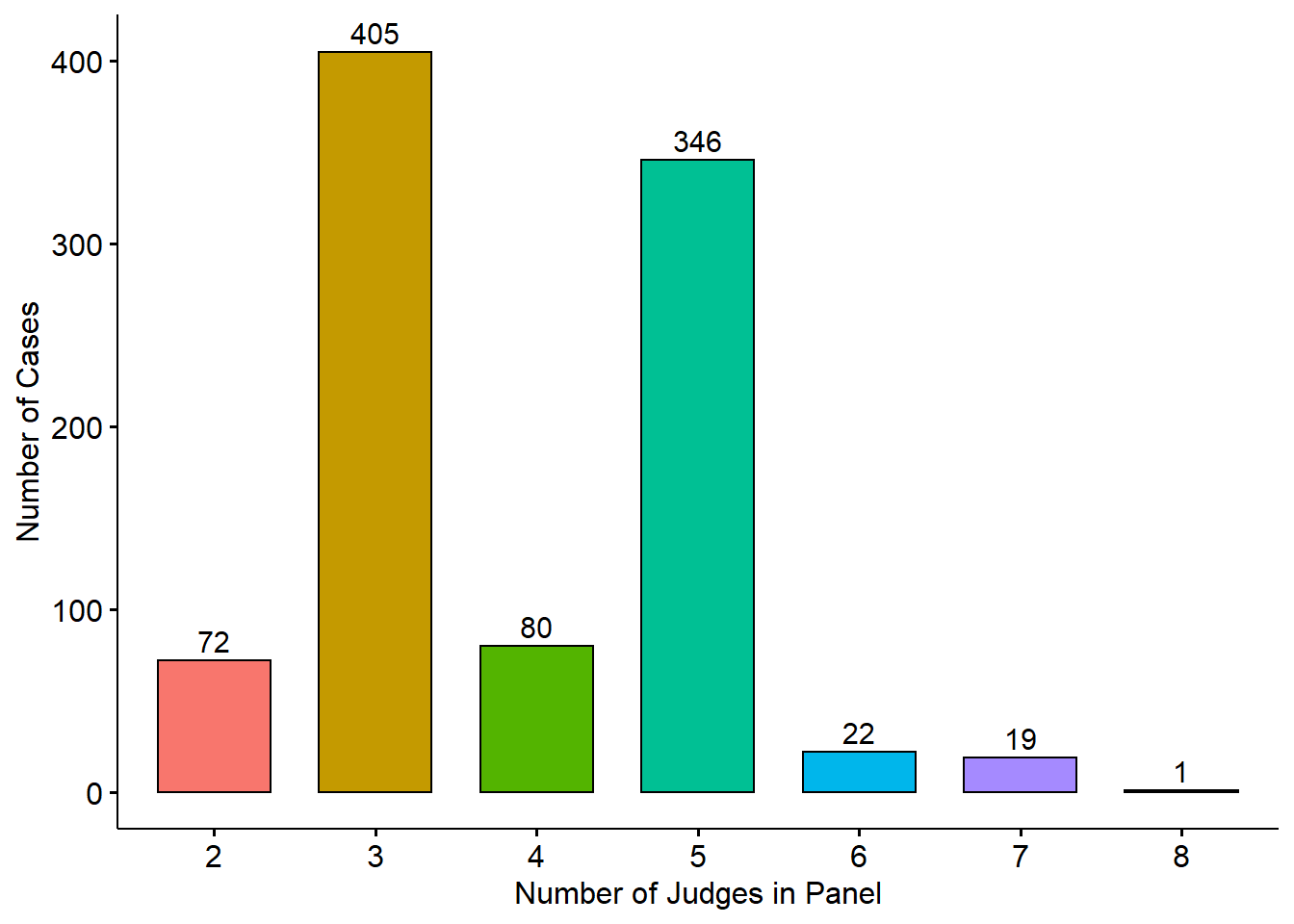

Beyond the division bench (two judge bench), the SCI currently sits only in odd-sized panels–3,5,7,9,11 or in one case a bench of 13 judges. The reason is obvious: an odd-sized bench ensures that there is no possibility of a judicial tie and consequently guarantees a resolution of the issue by a majority of the judges1. Odd-number panel formation is a gridlock prevention mechanism. However, when I printed a graph of the bench sizes in the first decade of the court, I found that we had benches of 4, 6, and even 8 judges.

Figure 1: Panel Size in the SCI from 1950-1959

There were as many as 22 6-judge decisions in the dataset. The norm in early cases heard by the Court was for all judges to sit en banc (as a full court) rather than in smaller panels for important cases. From its inception until the appointment of Justice N. Chandrasekhara Aiyar on 23rd September, 1950, there were only 6 judges in the SCI. All these inaugural judges sat en banc in important cases in the first year of the court, even though the resulting panel was even numbered. For example, the most famous case in India on preventative detention of A.K. Gopalan vs The State Of Madras was given by 6 judges. Similar is the case with Brij Bhushan and Romesh Thappar. This logic was not only limited to constitutional cases. For example, Messrs. Khimji Poonja And Company vs Shri Baldev Das C. Parikh related to a technical interpretation of an arbitration agreement and was heard by all 6 inaugural judges. In fact, most 6-bench cases are not constitutional cases. There are also several 4-judge bench cases, mostly dealing with income tax issues.

We see some panels of 6 judges even after the appointment of more judges. For example, The State Of Bombay vs Atma Ram Sridhar Vaidya was a 6-judge bench decision with Justice Aiyar but without Justice Mahajan. This was despite the fact that Justice Mahajan had participated in the deciding Keshavan Madhava Menon vs The State Of Bombay, a 7-judge bench decided just 3 days earlier. The last of the 6-judge benches was Kharak Singh vs The State Of U.P decided as late as 1962, when the court had 14 judges.

The sole 8-judge bench M. P. Sharma And Others vs Satish Chandra seems to be the last case following the norm of en banc panels for important cases. The case dealt with the legality of search and seizure as well as the right to privacy and is now mostly overruled by Oghad and Puttaswamy.

Seriatim Decisions

In most cases, courts in India have what can be called discretionary authorship, where authorship depends on the individual judges, who may “join” in the opinion of their colleagues or write separate opinions for themselves. This is different from many other courts. For example, the constitutional Court in Germany gives its judgement per curium (as a court) and does not disclose the authors of the opinion. As far as I know, the Ayodhya judgement is the only per curium decision of the SCI. On the other hand, the High Court of Australia follows seriatim decision-making, where it is compulsory for each judge who heard the case to disclose their vote through a separate opinion.

However, in atleast 3 cases in our dataset, I found the practice of seriatim decision making in the SCI. Consider Commissioner Of Agricultural Income Tax vs Sri Keshab Chandra Mandal, a 5-judge bench of the Court where Justice Das wrote the majority opinion and Justice Mukherjea wrote the lone dissent. The other 3 judges however did not join with Justice Das but wrote separate opinions with the words “I agree”2. Similar is the case with Tara Singh v State, a 4-judge bench where Justice Bose wrote the substantive opinion, while Justice Fazl Ali and Sastri wrote an opinion stating “I agree and have nothing to add”, and Justice Das wrote “I agree to the order proposed by my learned brother Bose”.

The cases were years apart, with several cases in between having discretionary authorship with judges simply joining opinions that they agreed with. It is unclear what led to this practice in these cases and why these particular cases have this pattern.

The Need to understand Process

These examples highlight how little we know about the internal workings of the Supreme Court of India. Without such a history, it is impossible to deconstruct the decision-making process of the Court. There are many more such norms that we do not know: norms regarding the selective publication of proceedings, norms regarding the selection of cases, norms regarding the allocation of oral hearing time etc. As Epstein and Knight have pointed out, each of these norms allows strategic choices by judges, and has an effect on final decision-making by the Court.

Part of the blame must lie with the Court itself, which has always been defined by opacity and which seems to have made no effort to document or archive its history. In any event, scholars of the Court must move away from the exclusive focus on its judgments and also examine the background processes that led to these decisions.

Many have suggested that an even numbered bench would better suit judicial compromise.↩︎

Similar was the case in N.P. Ponnuswami vs Returning Officer (1952)↩︎