Does fatigue affect decision-making and efficiency at the Supreme Court of India?

One of the most famous studies in judicial politics is Danziger, Levav, and Avnaim-Pesso’s work on the Israeli Parole board. The study concluded that food breaks affected the way that Israeli judges granted parole. Specifically, it found that the rate of granting parole drops gradually from 65% to nearly 0% for each session of the court and returns to 65% after the judges have had their break. The study suggests that this decrease can be attributed to either altered mood or mental depletion, with judges who were getting more tired and hungry taking the status quo option of not granting parole. The study has been challenged inter-alia for selection bias and overestimating effect sizes but remains highly influential.

Due to the sheer workload of cases, judges at the Indian Judiciary are even more likely to suffer from fatigue. According to a former Chief Justice of India, an Indian judge dealt with an average of 2600 cases in a year, compared to an average of 81 cases by American judges. Even in the Supreme Court of India, the highest court of the country, each panel hears an average of 46 cases for admission on miscellaneous days and 18 cases on regular days. If the theory of depletion is correct, we should particularly see the effect of fatigue in the decision-making of such high workload courts. In this note, I examine the effect of case fatigue on efficiency and decision-making at the Supreme court of India(SCI).

Methods

To do this, I use the Supreme Court Hearing Time Dataset, that I created along with Himanshu Agarwal. The dataset contains information about the hearing time of each case heard by the SCI between 20th January, 2016 till 5th December, 2016. To ensure homogeneity in case-type and to restrict the data-set to a manageable sample, I only look at Special Leave Petitions, the most common case-type in the SCI. This gives us a sample size of 23335 hearings. For each of these hearings, I downloaded the order of the court from the Supreme Court of India Website. Through a computer script, I classified the “winner” in each of these orders. All cases where notice was issued, leave granted, stay granted or appeal allowed were classified as petitioner wins.

As a measure of fatigue, I count the number of minutes that have passed from when the court convened till when the court heard a particular case. For example, if the court heard a case at 10:45 AM, 15 minutes after it convened at 10:30 AM, the number of minutes would be coded as 15. Unfortunately, for reasons related to the way the data was collected, we do not have the data for breaks including lunch breaks during the day. As a measure of fatigue, I use the amount of time that the court took for each individual hearing. The intuition here is that as the day goes on, the court needs to listen to more oral arguments in order to make their decision in any individual case1. Finally, as a measure of decision-making, I look at who was the winner in the individual hearing.

The assumption that we have to make is that the distribution of cases within a day is random or atleast exogenous to the time allocated to the case and the winner of the case. However, the cause -list is arranged in a way that cases which are being heard for the first time, for admission, are heard first, followed by cases which have been listed before. Presumably, hearings at the notice stage(first hearing) take lesser oral hearing time than hearings at the leave stage, which in turn take even lesser oral hearing time than hearings that occur after the court has granted leave to appeal. To account for this, I control for the stage of hearing through a variable which measures the number of times the case has been heard before. The SCI lists all admission matters for oral hearing on Mondays and Fridays. These are called “miscellaneous days”. Once cases are admitted, they are listed on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. These are called “regular days”. To account for this, I control for the day of the week. Assuming that there is no other systematic bias in the way that the cases are listed throughout the day, we can use regression methods to examine how fatigue affects the court2.

Results

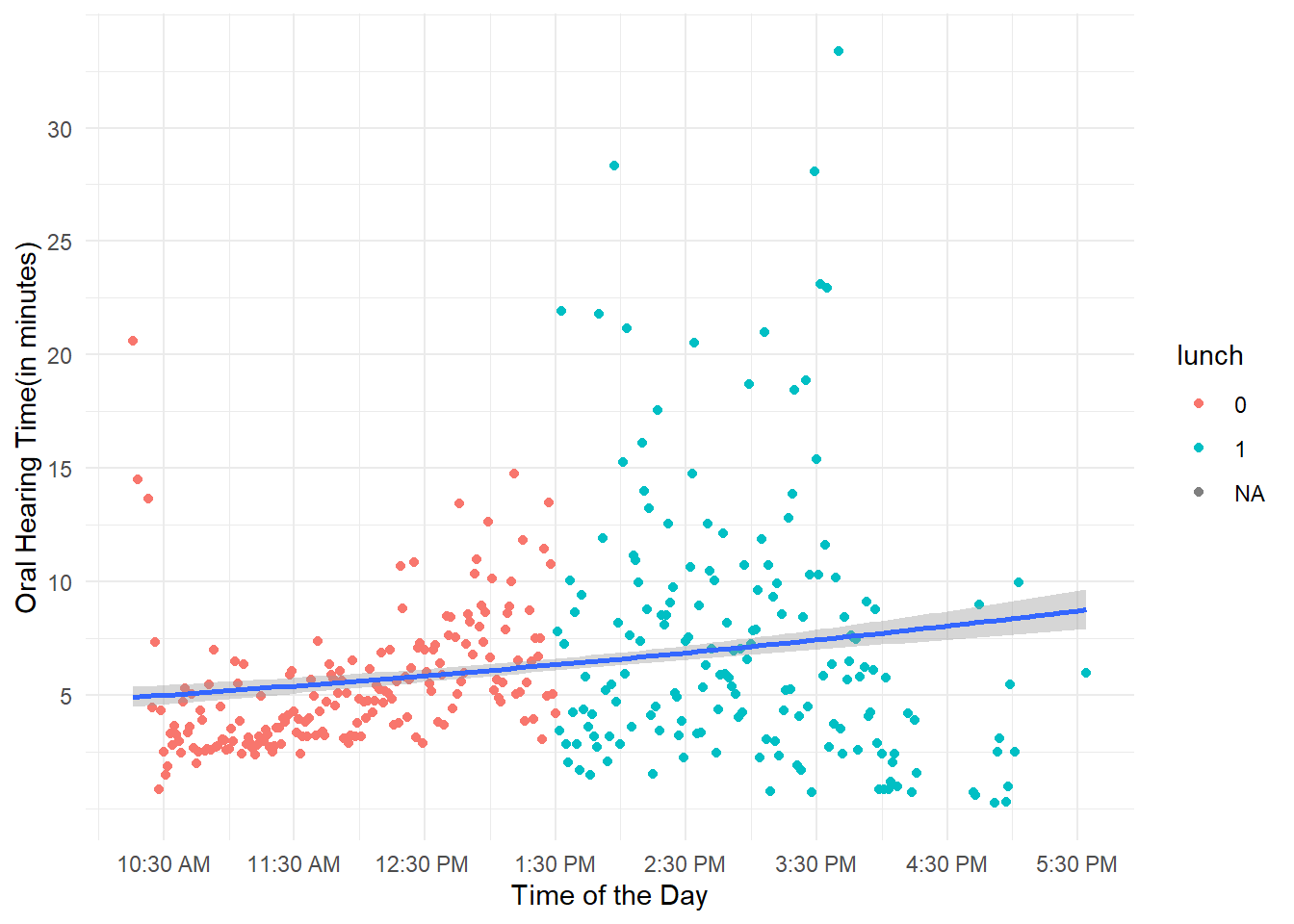

Figure 1: Oral Hearing Time in Miscellenous Days

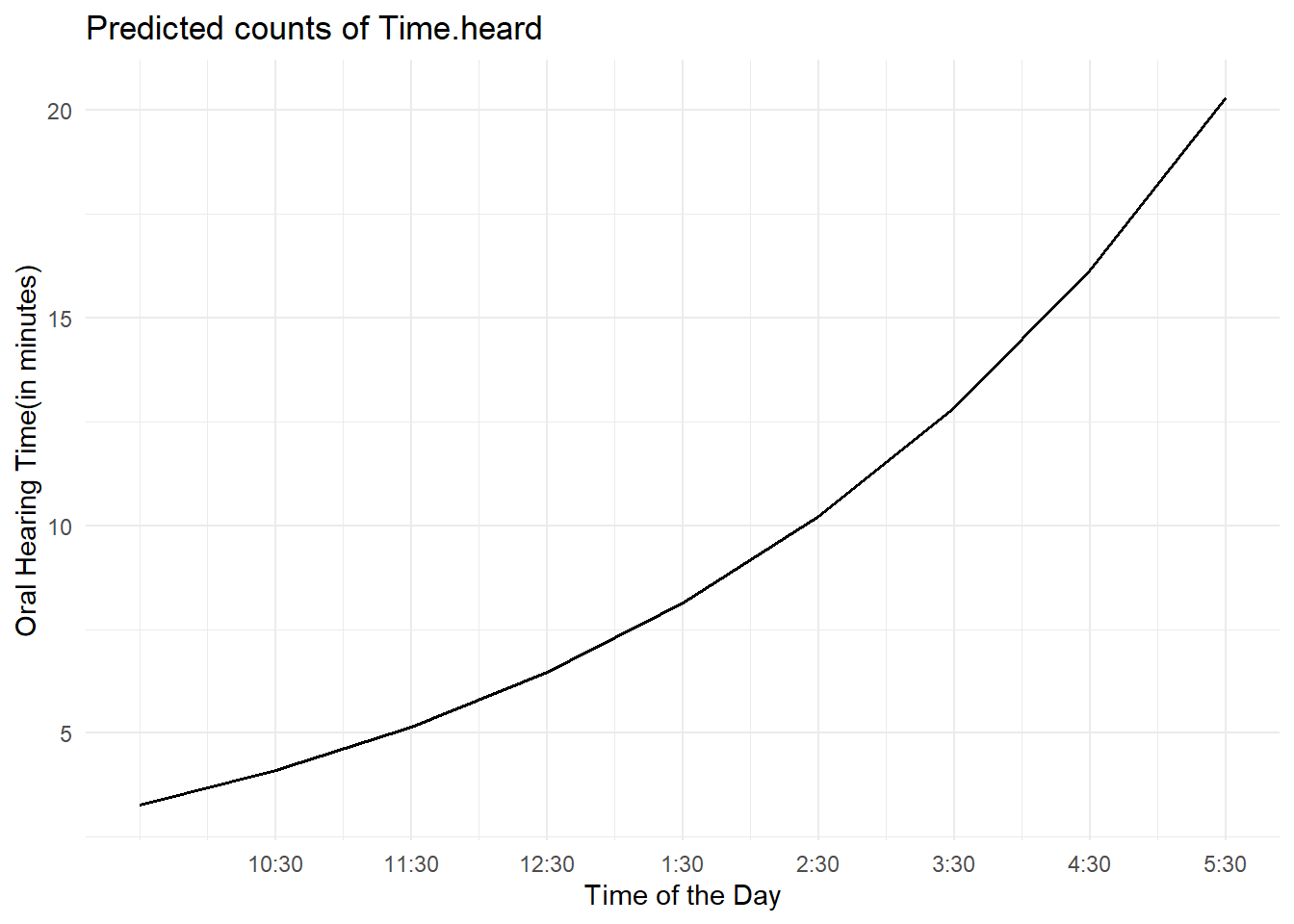

I find that oral hearing time allocated to a case is positively related to the time at which the case was heard (Table 1). As Figure 1 shows, average hearing time on miscellaneous days increases as the day goes on. It would seem then that as more cases are heard, the court becomes less efficient and takes more time to decide each individual case. As the marginal effects plot(Figure 2) shows,based on my model, a case heard when the court convenes at 10:30 am takes around 5 minutes of hearing time, while a case at the same stage of hearing at 4:00 pm takes 12 minutes, a 140% increase.

Figure 2: Marginal Effect of Time of the Day on Hearing Time

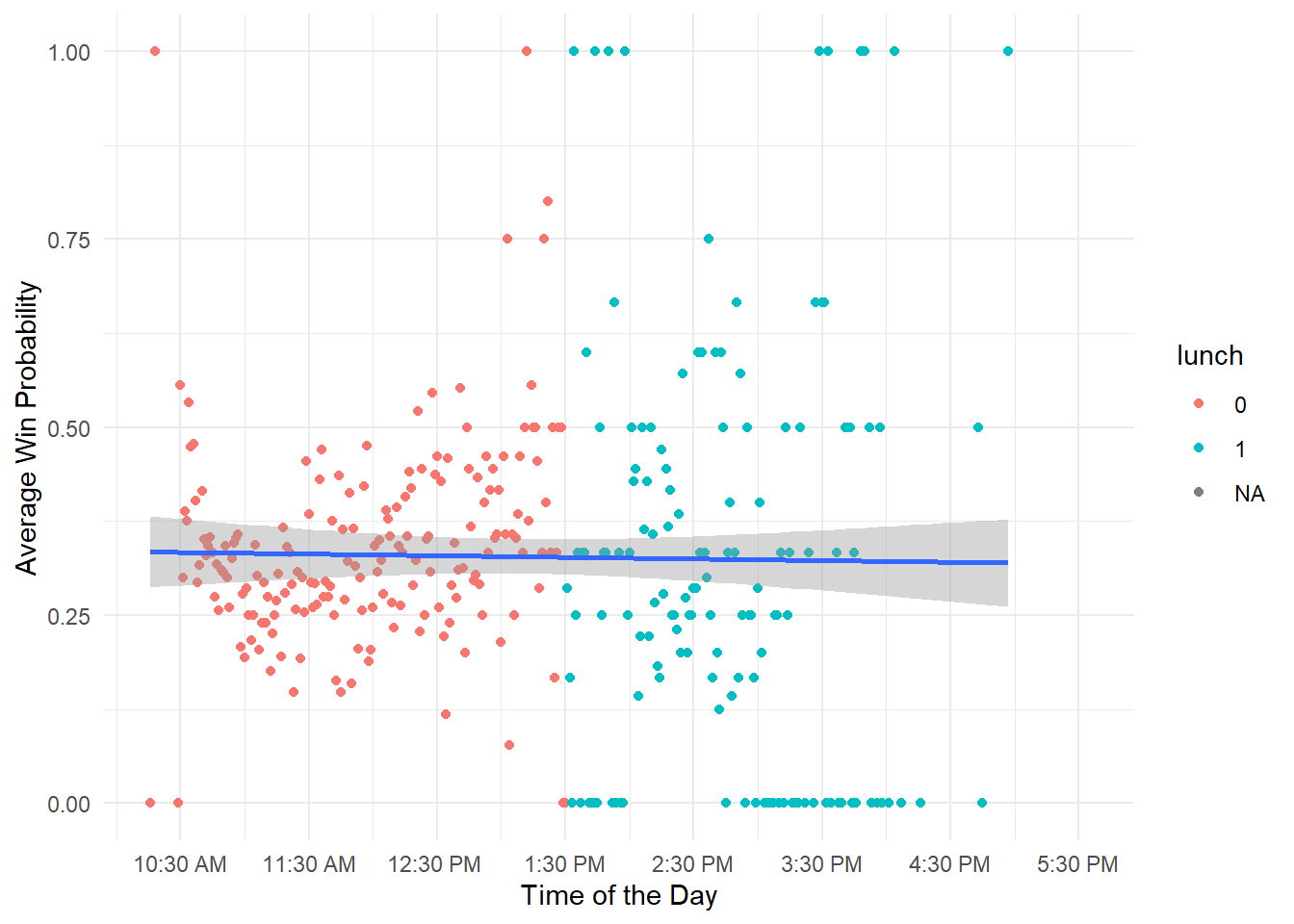

On the other hand, I find no evidence that decision making is affected by fatigue (Table 1). There is no statistically significant relationship between the time the case is heard and the winner of the case. As Figure 3 shows, the running average of a SLP succeeding in SC remains constant at around 31% at all times of the day on a miscellaneous day. I thus find no evidence that the SCI are more likely to choose the status quo option and dismiss petitions when they are tired.

Figure 3: Average Probability of Win on Miscellenous Days

These results change when I use an alternative measure of time of the day. Let us assume a cutoff for lunch at 1:30 PM. We can then measure the total time that has passed in each session. As an example, this measure would be 15 at both 10:45 AM and 1:45 PM. Regressing this measure with win probability leads to significant results, but in the opposite direction of our prediction(Table 1). It would seem that the court is more likely to reject petitions at the start of a session than the end of the session. Oral hearing time also increases as the session goes on. These results are not robust- particularly since our selection of the lunch cut-off time is entirely arbitrary– but lunch breaks do seem to matter in some way.

| Dependent variable: | |||||

| Time heard | Petitioner Winner | Time heard | Petitioner Winner | ||

| Poisson | logistic | Poisson | logistic | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Time of the day(hours) | 0.228*** | 0.025 | |||

| (0.0003) | (0.023) | ||||

| Time since last break(hours) | 0.097*** | ||||

| (0.035) | |||||

| Tuesday | 0.848*** | -0.144** | |||

| (0.001) | (0.069) | ||||

| Wednesday | 0.657*** | 0.300*** | |||

| (0.001) | (0.078) | ||||

| Thursday | 1.085*** | -0.073 | |||

| (0.002) | (0.126) | ||||

| Friday | -0.280*** | -0.053 | |||

| (0.001) | (0.052) | ||||

| Number of Previous Hearings | 0.007*** | 0.006*** | 0.006*** | 0.007*** | 0.007*** |

| (0.00002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.00002) | (0.002) | |

| Miscellenous Day | -0.672*** | -0.322*** | -0.331*** | ||

| (0.001) | (0.069) | (0.069) | |||

| Constant | 6.014*** | -0.575*** | -0.640*** | 5.550*** | -0.852*** |

| (0.001) | (0.072) | (0.075) | (0.001) | (0.040) | |

| Observations | 16,564 | 8,109 | 8,109 | 17,029 | 9,826 |

| Log Likelihood | -7,671,316.000 | -5,047.505 | -5,044.136 | -7,468,741.000 | -6,048.497 |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 15,342,640.000 | 10,103.010 | 10,096.270 | 14,937,494.000 | 12,109.000 |

| Note: | p<0.1; p<0.05; p<0.01 | ||||

The number of previous hearings in the case is also a significant predictor of whether a petitioner wins a case. The probability that a petitioner will win increases with each effective hearing of the case. This conforms to our intuition about the admission process in the SCI. As Khaitan(2020) and Chandra, Hubbard and Kalantry(2017) have pointed out, the court issues notice and grants leave to a limited number of petitions based on the chance that the petition will succeed. It is not a surprise then, that the further down the petition is in the litigation cycle, the more likely the chance that it will succeed.

Day of the Week Fatigue

I also looked at whether the day of the week in which the matter was heard affects either efficiency or decision-making. We would expect that the court allocates more time to cases on regular days and would also expect that petitioners are more likely to win on regular days.Depletion theory would also predict that the court is likely to be more fatigued when hearing cases on Monday, than on Friday where the judges are presumably fatigued from the work that happened during the week. Thus, judges should take more time to decide cases and be more likely to decide cases on Fridays than on Mondays.

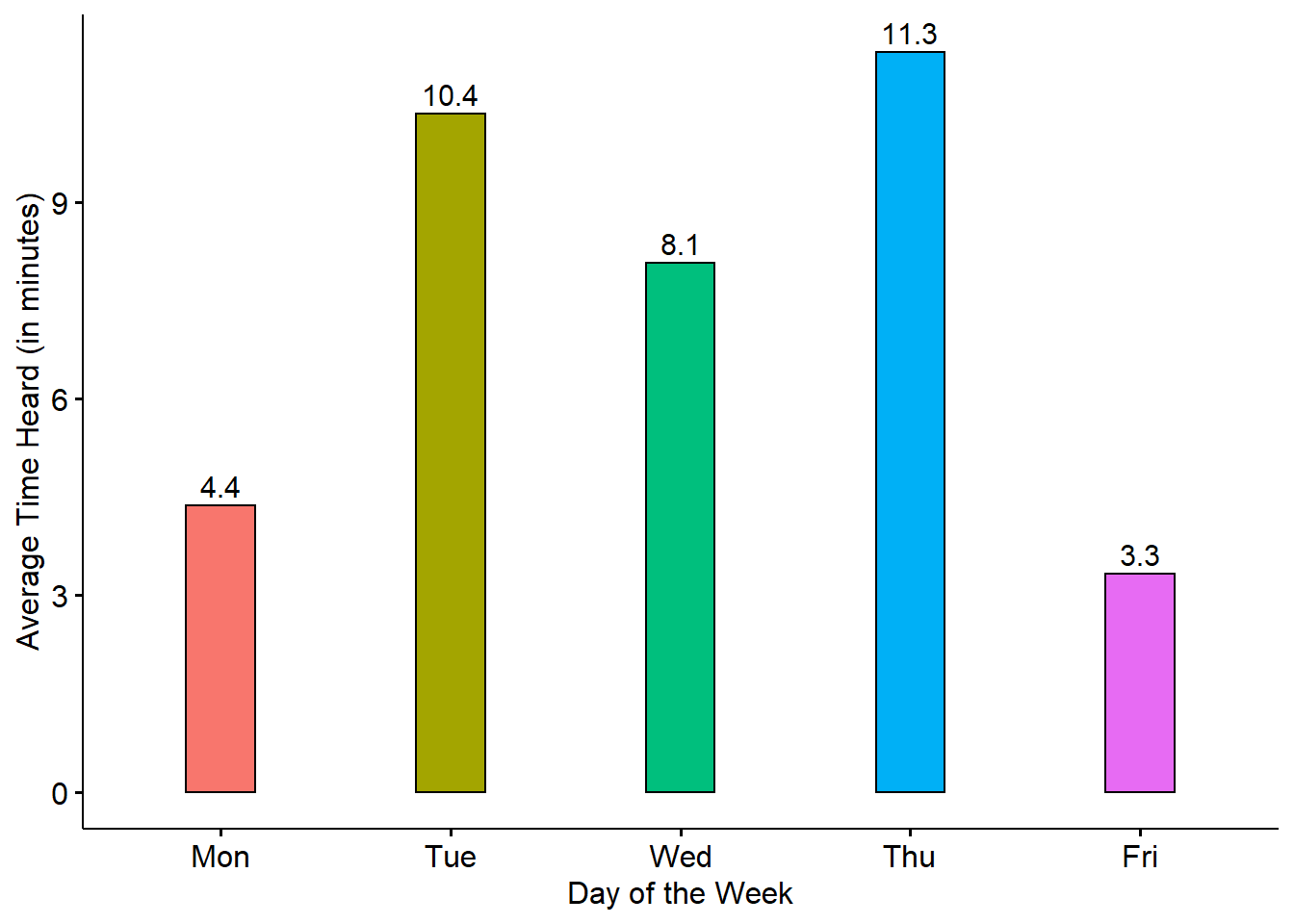

Figure 4: Average Hearing Time by Day of the Week

Like with the time of the day analysis, I find no evidence of any difference in win rates between the two miscellaneous days. However, as the figure 4 shows there is a significant differences between the hearing time across days. Contrary to the fatigue hypothesis, cases on Mondays, on average, are heard longer than cases on Fridays(Table 1). There is also a difference between the average hearing time on regular days. I don’t know whether this is representative of some difference in listing practices. The relationship remains significant on the addition of controls for subject matter and stage of hearing.

Discussion and Further Work

We find that while efficiency (the time it takes for completing a hearing) may change based on the time of the day as well as the day of the week, decision-making in the court remains unaffected by fatigue. There may be a few reasons for these results. First, unlike the Israeli parole board, judges of the SCI have the discretion to simply adjourn or pass-over the case. When they are fatigued, it is possible that judges intentionally adjourn cases that they believe will take more effort and time. Second, we only tested a limited timeline, and did not control for judge-level effects. It is possible that some judges thrive under the high workload while others are pressured by it. Third, fatigue might have indirect effects- for e.g. the court might dictate orders of lower quality when under pressure. I hope to examine a few of these questions in future posts.

It is also possible to theorize the opposite hypothesis– judges may take less time for each case when fatigued, since they would like to default to status-quo.↩︎

For the efficiency model, I use poisson regression to regress time heard with time of the day. For the decision model, I use logit regression to regress winner(1 for petitioner,0 for other) with time of the day. In each case, the number of prior hearings in the case as well as a dichotomous variable for whether the case was heard on a miscellaneous day.↩︎