Determining the Criteria for Appointment of Judges to the Supreme Court of India

On 17th August 2021, the collegium recommended the names of 9 new judges for the Supreme Court of India (SCI) to the government. Many hailed the recommendation, which proposes the name of 3 women judges, as a historic step towards gender equality in the Court. Others have criticized the decision for not including the name of Chief Justice Akil Kureshi, alleging that the collegium had given in to government pressure. Both camps, however, were basing their conclusions on conjecture. We neither know whether the court had gender in mind while selecting the list nor do we know whether Justice Kureshi was not selected due to government pressure. Since the SCI collegium does not give public reasons for its recommendations, we simply do not know the criteria that the SCI uses to appoint judges.

Existing Studies and Counterfactual Problems

There have been several attempts at understanding the criteria for judicial appointments. For example, Gadbois, through extensive interviews with Judges and their families, was the first person to be able to construct short biographies of Judges in the SCI from 1950-1989. Using these, Gadbois showed that while the official criteria for the appointment of SCI judges was broad, the average SCI judge was likely to be selected based on region, experience, and socio-economic characteristics. Gadbois described an archetypal Judge in the SCI as a upper-class Hindu Brahmin who had served as a former High Court Chief Justice. Expanding Gadbois’ study to Judges appointed till 2013, Chandrachud also attempted to map the informal factors which affect the appointment of judges. Through the use of both public biographies of judges as well as interviews, Chandrachud argues that the most important criteria for appointment as a SCI judge was their experience as a High Court judge as well as the regional diversity of the SCI. The more senior a high court judge and the less represented their parent high court on the SCI, the higher the chance of elevation.

Recent work has reiterated the sailence of these criteria. In their recent article, Chandra, Hubbard and Kalantry show that the advent of the collegium system led to a very little change in the biographical characteristics of judges appointed to the SCI. The only noticeable change is that post-collegium SCI judges are more likely to be from private practice and spend more time as high court judges than judges appointed before the advent of the collegium system. Kumar also posits that the SCI prefers people who practiced for some time rather than those who served in the lower judiciary. Fayiz and Saxena argue that the court mostly appoints Hindu Upper Caste judges.

Apart from the Gadbois’ interviews, these studies rely on public biographies of the judges available on the SCI website. Yet, as Tripathy & Bagga demonstrate these official biographies are often incomplete and lack crucial socio-economic information about the judges. Even assuming that these biographies were complete, there is an inherent limitation to the use of biographical information of appointed judges to infer the criteria that was used to appoint them. Unfortunately, we do not know whether the things we happen to observe in the biography of SCI judges are related to their appointment. Take, for instance, the case of a hypothetical Judge A, whose parent high court is Allahabad High Court, the largest high court in India. Let us assume the SCI, which has no judges from the Allahabad High Court, appoints Judge A. Can we conclude that Judge A was appointed due to her parent high court? No. Judge A may have been chosen because she was perceived to be a good judge or because she was simply the senior most judge in the all india high court roster.

This is known as the counterfactual difficulty of causal inference. Without knowing the counterfactual– in this case whether Judge A would have still been appointed had she not been a part of Allahabad high court– we cannot make conclusions about the role of the parent high court in the appointment process. In most cases, it is impossible to study a counterfactual in real world settings- after all we cannot go back in time and assign Judge A to another high court. One approximation method that we use often in social science to mimic this process is called Matching. In matching, we try to find Judge A’s twin, say Judge B, who is similar to Judge A in all respects, except the parent High court. Let us assume now, that Judge A was appointed and Judge B was not. In this case, since the parent high court was the only difference between the two judges we can conclude that it is a criteria for appointments to the SCI. Let us for the moment ignore the extremely difficult empirical problem of finding a “similar” non-appointed counterpart to all the judges in the SCI. What should be apparent is that to even theoretically attempt this exercise, we need not only the biographical characteristics of all judges of the SCI who were appointed but also the biographical characteristics of all candidates who were not appointed. If we assume all candidates are high court judges, to truly understand the appointment process, we would need the biographical characteristics of all high court judges.1

Collegium Resolutions

There is ofcourse, another simpler way of knowing the criteria for appointment of judges–simply asking the people who select the judges.2 In the case of the SCI, this is the Chief Justice and after 1993, the collegium. Till now however, the Gadbois interviews remain the only place where we have judges commenting on the appointment process. Even this is mostly anecdotal and limited to particular judges. Beyond the rhetoric of seniority and merit, Chief Justices have remained silent on the general criteria they use for selecting judges in the higher judiciary. This is why the publication of collegium resolutions was an extremely important development in our understanding of the judiciary. On October 3rd, 2017, the Supreme Court Collegium in a historic move resolved that the reasons for its decisions on the appointment of Judges will be uploaded to the Supreme Court’s Website.The resolution then was seen as a break from the past which would “maintain and enhance public confidence in the integrity and impartiality”.

These public resolutions marked the first time that the SCI gave public reasons for its appointment decisions. They were not verbatim minutes of the collegium meetings, but were still very revealing. In the first of its resolutions, for example, the court listed several criteria which it used for the appointment of high court judges. For judges appointed to the high court from the bench, the main criteria was seniority and the report of the judgement committee about their lower court judgments. For judges appointed from the bar, there was an objective criteria for age and income. In both cases, the judges took into account the reports of the Information Bureau on the integrity and professional image of the candidate. In some cases, the candidate was called for an interview. What was even more interesting was that the court gave the list of all potential candidates suggested by the High Court as well as specific reasons for why a candidate was rejected. These criteria may not have been exhaustive, but still allowed public engagement with the appointment process.

The resolutions for the Supreme Court appointments were unfortunately not as detailed. The only clear criteria expressly considered for SCI appointment was the all-india seniority rank of the judge as well the parent high court. Other than this the resolutions simply stated that the collegium had simply stated that it had taken into consideration “all relevant factors”. The SC appointment resolutions also did not contain information about the candidates considered and rejected.

The publication of these detailed resolutions, however, did not last long. Soon after the resolutions started being published, letters from Justice Lokur and Justice Joseph, two members of the collegium, were leaked to the press. Justice Joseph’s letter expressed concern about listing specific reasons for the rejecting candidates, arguing that the information may “violate human rights of some persons”. After this leak and presumably after discussions with collegium members, the uploaded resolutions stopped containing specific reasons for the rejection of particular candidates. When a candidate was to be rejected, the resolutions now simply stated they were rejected due to “material available on record”.

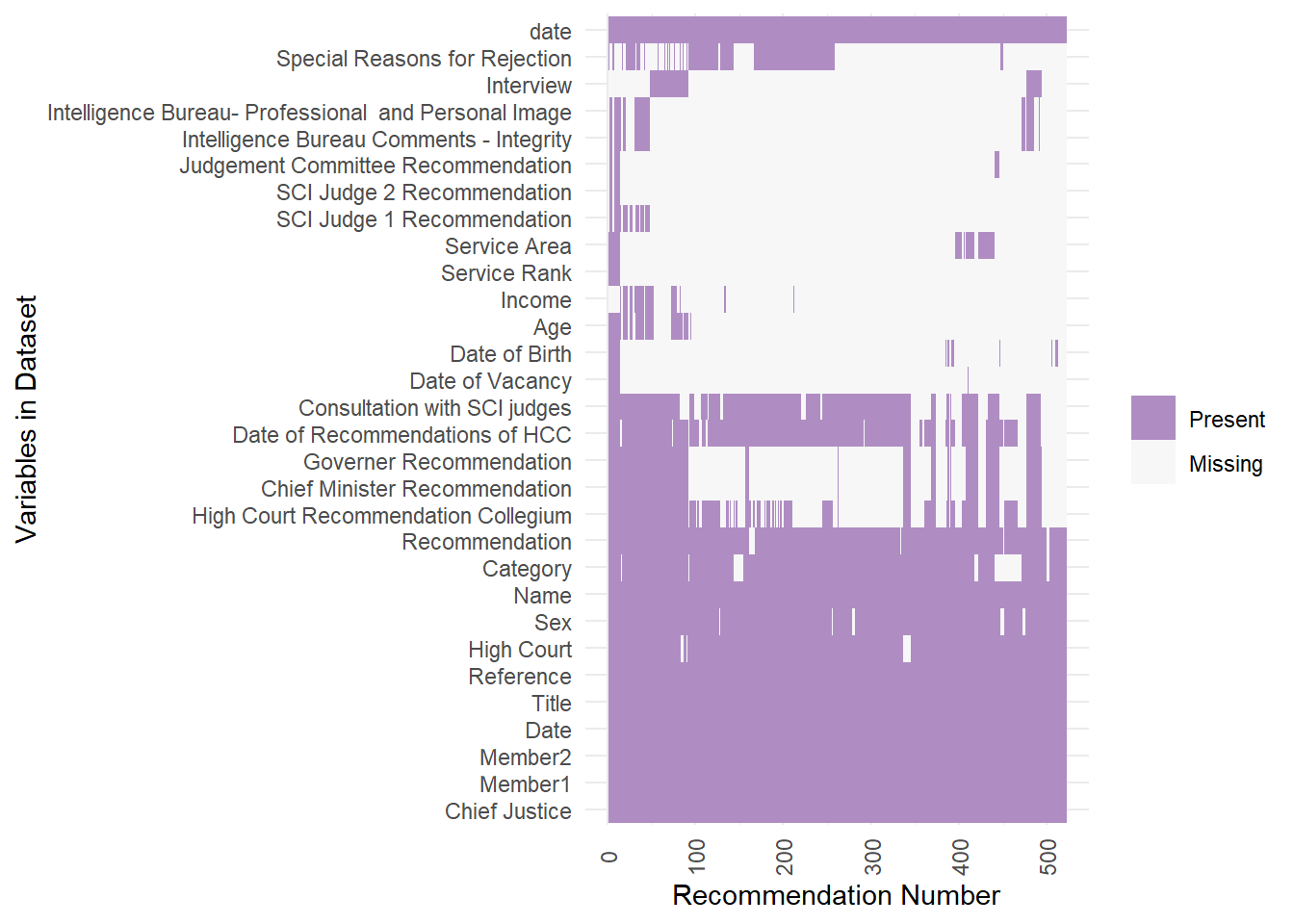

Figure 1: Missingness Map of SCI collegium Resolutions for Appointment of High Court Judges

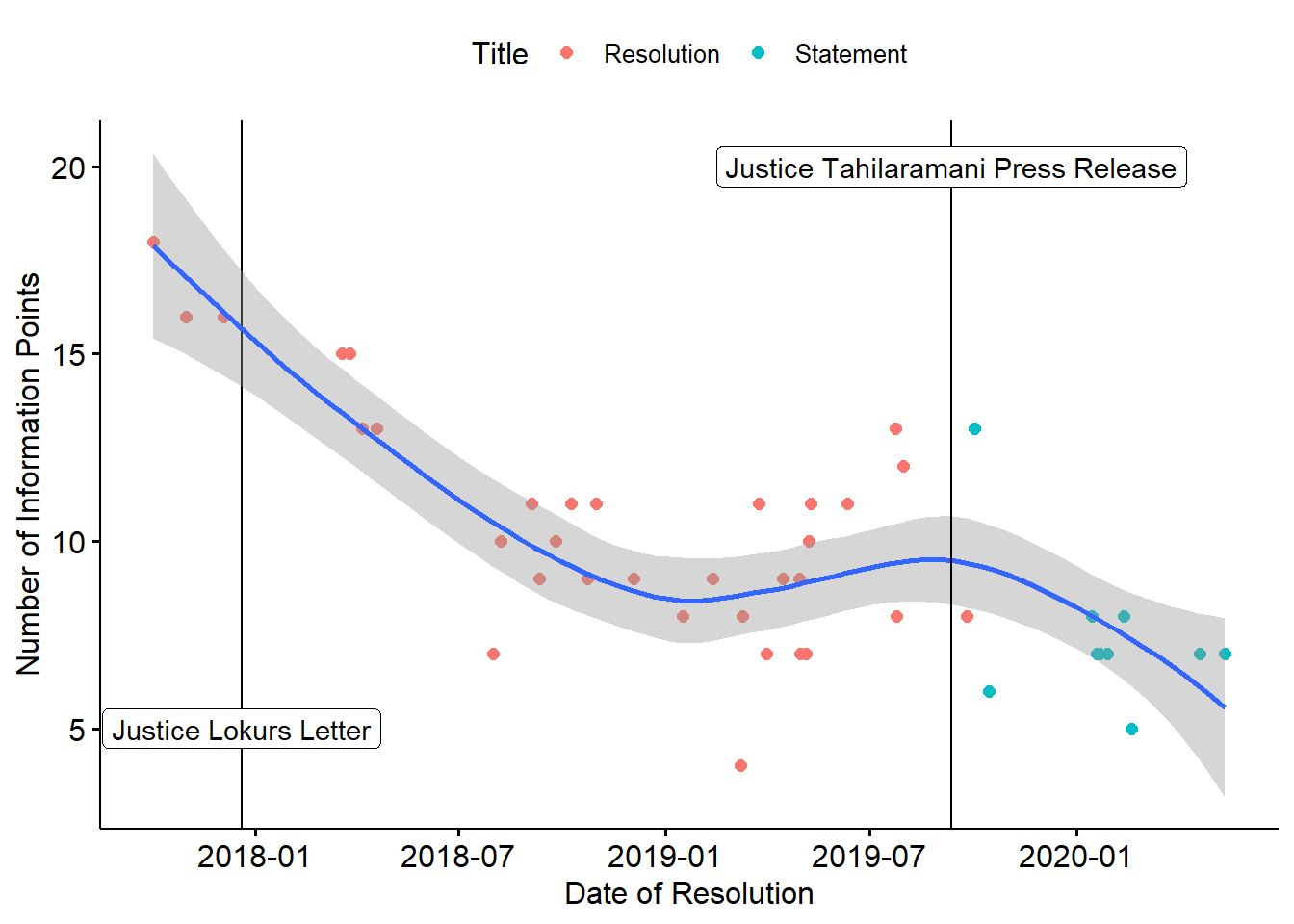

To understand the criteria discussed in each of these resolutions, I built a dataset of all collegium resolutions till April 20203. Figure 1 maps changes in the criteria and information given in all collegium resolutions for the appointment of High Court judges. As can be seen, the court gradually stopped giving us information about selection criteria and eventually stopped giving information about each individual candidate altogether. Figure 2 shows the the decline in the number of information points available in each resolution. Within a span of 2 years, the moved from a high of giving 25 information points in each resolution to a low of only 5. The final blow to these detailed resolutions came when a particular collegium decision to transfer Chief Justice Tahilramani and Justice Akil Kureshi was discussed and critiqued in the media. The resolution stated that the transfer was required, “in the interest of better administration of justice, a phrase that had also been used in all prior resolutions recommending transfers. After the heightened media scrutiny questioning the reasons for the transfer, the court released a statement, stating that the decision was made due to “cogent reasons” and “it would not be in the interest of the institution to disclose the reasons for transfer”. Since then the court has chosen to publish only “statements” instead of resolutions, which now only have the names of recommended candidates. It would seem then that the increased public scrutiny and criticism of its decisions, forced the court to revisit its initial move towards transparency. Whenever the court faced a public challenge to its appointment decisions, its response has been to hide how that decision was made. This, as Kumar puts it, “ smacks of institutional cowardice”.

Figure 2: Number of Information Points in SCI collegium Resolutions for Appointment of High Court Judges

Bickel in his famous book The Least Dangerous Branch coined the term “the counter-majoritarian difficulty” to describe the fact that in the U.S, an unelected judiciary reviews legislation from the popular branch of government. The counter-majoritarian difficulty is even more pronounced in the SCI- which is the only case in the world where the judiciary appoints its own members and also does not publicly disclose how it makes these appointments. The judges in the Indian higher judiciary are thus not only unelected but also cliquish. Given the central place of the court in deciding the country’s polity, the court’s opacity should be particularly concerning.

As far as I know, Justice Hub’s Summer of Data program is attempting to do this. This is difficult, since public data sources of High Court Judges biographies are extremely sparse.↩︎

The assumption here is that the judges will be sincere in revealing such criteria. We, however, know that judges have strategic incentives to reveal the most uncontroversial criteria.↩︎

I thank Gauri Balagopal, Tanvi Raina, Sanjitha Umapathy for their assistance in the creation of this dataset.↩︎